Taking aim at George W., a populist agitator makes noise, news and a new kind of political entertainment

By RICHARD CORLISS /

TIME

"Was it all just a dream?" Michael Moore poses that question at the start of Fahrenheit 9/11, his docu-tragicomedy about the Bush Administration's actions before and after Sept. 11, 2001. Moore's tone isn't wistful; it's angry. He's steamed about the Florida vote wrangle of 2000, the Supreme Court decision to declare George W. Bush President of the United States, the policies of Bush's advisers and especially what he sees as the deflection of a quick, vigorous search-and-destroy mission against Osama bin Laden into an open-ended war on terrorism—"You can't declare war on a noun," Moore said last week—that spawned a dubious and costly invasion of Iraq.

Now, after a week in which his film became the highest grossing documentary of all time— and more than that, a nationwide rally point for Bush opponents, a red flag for Bush supporters, a cinematic teach-in for the undecided and a potential factor in the '04 presidential race—Moore may well be asking, "Is this all a dream?" For starters, is this the same film that not long ago was an orphan? In May a controversy-averse Walt Disney Co. ordered its subsidiary Miramax Films to dump the movie. But just weeks later Fahrenheit 9/11 copped the Palme d'Or (first place) at the Cannes Film Festival and eventually found other distributors, an indie coalition of the willing. By that time, the picture's incendiary charges and Moore's reputation as a folksy firebrand of the left had already begun to ignite accusations that he had twisted facts to suit his politics. Faster than you can say, "That's the kind of publicity no amount of money can buy," Fahrenheit 9/11 had become a secular Passion of the Christ and the most hotly debated political film since Oliver Stone's JFK 13 years ago.

But whereas JFK merely spun conspiracy theories about a dead President, Fahrenheit 9/11 goes after a sitting one with the explicit goals of unmasking his supposed crimes and removing him from office. Back when political bosses picked candidates and the rules of the game were arbitrated by newspaper editors and three network anchormen, for a mere movie even to attempt such a thing would have seemed folly. Today people get their news and, just as important, their attitudes from more rambunctious sources— the polarized polemicists on talk radio and cable news channels, comedians and webmasters. That's poli-tainment, and as practiced by Rush Limbaugh and other right-wing hosts on radio and by Matt Drudge on the Internet, it hounded Bill Clinton's presidency while spicing and coarsening the standards of political discourse.

In Moore the left wing has now found its own Falstaff of the political revels, a figure who can punch as hard and fast—and as recklessly?—as anybody the right has to offer. And Fahrenheit 9/11 may be the watershed event that demonstrates whether the empire of poli-tainment can have decisive influence on a presidential campaign. If it does, we may come to look back on its hugely successful first week the way we now think of the televised presidential debate between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon, as a moment when we grasped for the first time the potential of a mass medium—in this case, movies—to affect American politics in new ways. If that's the case, expect the next generation of campaign strategists to precede every major election not only with the traditional TV ad buys but also with a scheme for the rollout of some thermonuclear book, movie, CD or even video game, all designed to tilt the political balance just in time.

Fahrenheit 9/11 may also be branded as the film that made an overblown case against the Bush team. Certainly defenders of the Iraq war are already casting it that way. Limbaugh calls it "a pack of lies." In the online publication Slate, Christopher Hitchens wrote that it was "a sinister exercise in moral frivolity, crudely disguised as an exercise in seriousness." Even liberal Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen, an opponent of the war, told his readers that he "recoiled from Moore's methodology." To mount fast responses to critics like those, Moore has organized a "war room" overseen by former Clinton White House aides Chris Lehane and Mark Fabiani. He also hired the former chief of fact checking at the New Yorker magazine to comb the film for inaccuracies. "There's lots of disagreement with my analysis of these facts or my opinion based on the facts. But," he insists, "there is not a single factual error in the movie. I'm thinking of offering a $10,000 reward for anyone that can find a single fact that's wrong."

Whatever the film's merits as a reliable account of recent history, for months to come pollsters and political consultants will be analyzing and focus grouping the viewer/voter response to Fahrenheit 9/11, struggling to measure its real impact on their thinking (and voting). But the R-rated film has taken the first important step toward being a political weapon of consequence by becoming an indisputable box-office phenomenon. In its first weekend, it torpedoed all predictions and earned $23.9 million, instantly passing Moore's Bowling for Columbine as the all-time top-grossing documentary (excluding IMAX spectacles). Fahrenheit 9/11 last weekend passed $50 million. Miramax's Harvey Weinstein predicts a $100 million gross in the film's first three weeks.

Though it has aroused viewers in sharply different directions—in one Internet moviegoer poll, 64% gave it an A rating, 30% an F—the film has also found audiences across the range of America, in big towns and small, blue states and red. It attracted mostly men its first Friday night, mostly women on Saturday. Exit surveys show that as the week wore on, it even became a date picture. ("That's a good idea," Moore says, "especially if it's a first date, because you'll have plenty to talk about. And also you can vet the date. You'll know right away if you should have a second date.") And thought it wasn't a date, last week, the day before a big race in Sonoma, Calif., racer Dale Earnhardt Jr. even took his crew to see the movie.

From his debut movie, Roger & Me, which detailed his attempt to confront General Motors boss Roger Smith about the social effects of closing a GM plant in Moore's hometown of Flint, Mich., the filmmaker has been America's pre-eminent populist pest. He has taken on Nike's Phil Knight over factory conditions and the N.R.A. and America's gun love. Fahrenheit 9/11 considerably ups his nuisance value: he is after a President's foreign and domestic policy, and Moore is not cowed. "I come from a factory town," he says, "and you don't go to a gunfight with a slingshot." Moore shoots only with a camera, but it's loaded.

"I'm not just preaching to the choir. And it's not just the choir giving the ovation. I've got letters from a bunch of Marines who went to see it at a theater near Twentynine Palms, Calif. A church group in Tulsa went to see it and was incredibly moved. There was a Republican woman in Florida unable to get out of her seat, crying."

You would have expected Moore's movie to play well in the liberal big cities, and it is doing so. But the film is also touching the heart of the heartland. In Bartlett, Tenn., a Memphis suburb, the rooms at Stage Road Cinema showing Fahrenheit 9/11 have been packed with viewers who clap, boo, laugh and cry nearly on cue. Even the dissenters are impressed. When the lights came up after a showing last week, one gent rose from his seat and said grudgingly, "It's bull____, but I gotta admit it was done well."

In the press, Fahrenheit 9/11 has made news with its assertions of White House duplicity. But in theaters, the movie can hit home, especially for those who have loved ones in Iraq. Greg Rohwer-Selken, 33, of Ames, Iowa, and his wife Karol are former Army reservists who both volunteered for Afghanistan (but weren't sent). Now Karol is serving in the National Guard in Iraq. After seeing Fahrenheit 9/11 in Des Moines, Rohwer-Selken wipes away tears as he says, "It really made me question why she has to be over there." (The Army and Air Force Exchange Service, which books films to be shown on military bases around the world, has contacted Fahrenheit's distributor to book the film.)

The first week's release no doubt attracted a higher proportion of its natural constituency, the liberal base. To become a blockbuster and a shaping force in the presidential campaign, Fahrenheit 9/11 will have to entice the curious, the hostile, the indifferent—just as a politician's toughest job is to reach the large number of nonvoters. Moore keeps saying that America is "a 50/50/50 country. There are those who vote, who seem to be evenly split, but then there's the 50% who don't vote, and no one pays attention to them." Moore does. He's doing what he does best—pestering—to get them into theaters. And then to the polls.

"I didn't have any of this so-called success until I was 35 years old with Roger & Me. Up until that point, I never made more than $15,000 a year. When you spend the first 17 years—in other words, half—of your adult life earning $15,000 or less, it really doesn't matter what kind of success you have after that. It's so ingrained in you."

His own life story would make a pretty cool movie. The son and nephew of GM factory workers, Moore was educated by nuns and Jesuits, and at 14 he briefly attended a seminary and had thoughts of becoming a priest. Eagle scout; expert hunter; good student. After disagreeing with a policy at his high school, he ran for the Davison County school board—and won, making him, at 18, one of the youngest elected officials in the nation.

Moore later dropped out of the University of Michigan at Flint and set up a crisis-intervention center. At 22 he joined, then edited, an alternative paper, The Flint Voice, while the industrial economy flailed and local jobs went overseas. "During the Reagan years we sat there in Flint and watched the Democratic Party cave in," he says, "watched the liberals be weak-kneed and wimpy and never stand up and fight for us. Liberals have failed us, the working people of this country." His stern ideals and prickly temper shortened some of his work stints: as editor of the left magazine Mother Jones (a job that lasted less than a year) and author of Moore's Weekly, a newsletter that critiqued the media and was partly financed by Ralph Nader. Maybe only a tough man could make such confrontational comedies. He has won the allegiance of one tough man, Weinstein, who says, "Michael walks to his own beat. He has to when he wakes up every day and has a new death threat. I love the guy, and I'm not saying that 'Hollywood style.' I'm saying that for real."

Moore's debut film, 1989's Roger & Me, made for $250,000, was bought by Warner Bros. for $3 million. It earned nearly $7 million at the box office and introduced audiences to an improbable movie star: a shaggy, cagey doofus with a killer instinct for political and comic agitation.

Other filmmakers might have followed Roger & Me's success to Hollywood. Moore did direct one fiction comedy, Canadian Bacon, starring John Candy, but he realized that his true status was as the outsider banging down the doors of the insiders. He hatched a political show, TV Nation, which somehow managed to run at one time or another on nbc, Fox and Comedy Central. His 1997 film The Big One took a smart swipe at Big Business.

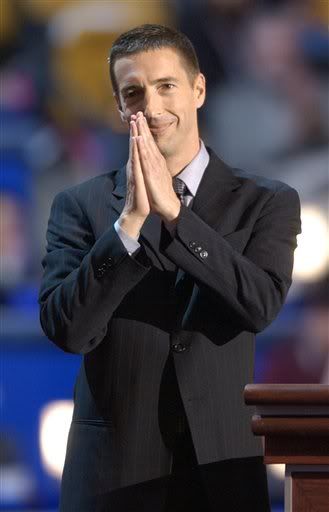

In Bowling for Columbine, he amplified his vision into an essay on the U.S. murder rate and attached it to a tragedy: the murder of 12 children and one teacher at a high school in Littleton, Colo. When he was given the Oscar for best documentary, Moore declared, in front of an uneasy audience and a billion TV viewers, "We live in fictitious times. We live in the time where we have fictitious election results that elect a fictitious President. We live in a time where we have a man sending us to war for fictitious reasons ... Shame on you, Mr. Bush. Shame on you."

The speech won him icy stares and undeniable celebrity as a fearless am-Busher. It helped propel his books Stupid White Men and Dude, Where's My Country? to the top of the best-seller lists. And it provided the emotional foundation for his latest, most audacious film. (At Cannes, Quentin Tarantino called Fahrenheit 9/11 "the first movie ever made to justify an acceptance speech.") By now Michael Moore, lone wolf, has morphed into Michael Moore Inc. And also Michael Moore, target. He is the subject of a book-length blast from the right, Michael Moore Is a Big Fat Stupid White Man, and a forthcoming documentary, Michael Moore Hates America. In political if not economic power, he is as big as the guys he used to track down.

"I went to The Passion of the Christ on the second night, and there were two people speaking in tongues; other people had their rosary beads out. In this country 50% of the people go to church on a regular basis. And they went to that movie. My film has a much broader cross section of moviegoers—people from the general public."

Fahrenheit 9/11 is The Passion of the Christ of the left. Both films established a base in a devoted minority: the evangelical right and the political left. Both films were attacked in the major media and profited from it: the faithful were galvanized, the films got an underdog status, and uncommitted moviegoers paid attention. As church groups recruited members to attend Mel Gibson's film its first weekend, so too the liberal lobby MoveOn.org signed up 110,000 members who pledged early attendance at the Moore movie.

Hit movies typically breed clones. And in this election year, with stakes and tempers high, a potent nonfiction genre is emerging: the agit-doc, dealing with high-octane political issues, often in a confrontational tone. Trailing Moore's box-office clout, agit-docs are surging into the mainstream. One of them, The Hunting of the President, co-directed by Clinton pal Harry Thomason, was originally to go to 30 theaters; now its distributor has revved that number to 125 and has put the film's trailer on many screens showing Fahrenheit 9/11.

"We've underestimated the audience's desire to see [political] material," says Robert Greenwald, director of Uncovered: The War on Iraq, a sober and devastating critique of Bush's foreign policy. "I don't think it's about hating the President. It's that politics has been brought home to the deepest part of ourselves. People now feel Politics Is Me."

"I don't like this film being reduced to Bush vs. Kerry. The issues in it are larger than that ... When Clinton was President, I went after him. And if Kerry's President, on Day Two I'll be on him."

Fahrenheit 9/11 wants to reach a drowsy electorate—most of whom don't bother to vote—to rouse them with a jazzy reveille of facts and innuendos and get them involved. "There's millions of you on the sidelines," Moore notes, "and I'm like the coach saying, 'Come on, bench, get in the game!'" And play for which side? That's easy to guess. Moore's mantra is that he made the film to prevent Bush's re-election—or, as many Democrats would say, election, given that they believe the first time he was appointed by the Supreme Court.

To combat Fahrenheit 9/11, White House communications director Dan Bartlett quipped at a press briefing, "If I wanted to see a good fiction movie, I might go see Shrek or something, but I doubt I'll be seeing Fahrenheit 9/11." Otherwise, the Bush team's policy is public silence. "We thought about what they would want us to do," says a top adviser, "and then we did the opposite." Moore does not spare the Democrats entirely in his film. Most Democratic Senators, including Kerry, not only voted for the Iraq war but until recently refused to criticize the President's decision to invade. Among the clips in Fahrenheit 9/11 is one of minority leader Tom Daschle last year urging other Senators to follow his lead and vote for Bush's Iraq war. Two weeks ago, at the Washington premiere, Moore sat a few rows behind Daschle. Afterward, says Moore, "he gave me a hug and said he felt bad and that we were all gonna fight from now on. I thanked him for being a good sport."

The Democrats may not know yet how closely they want to embrace a film that sometimes lunges at Bush without regard for niceties of context and counterargument. Democratic moderates may find Moore's style too extreme, pugnacious, rabble-rousing—even if his intention is to rouse the rabble to vote the Democrats back into office. So as Kerry strategists move their man to the center, they hope to benefit from the Fahrenheit 9/11 phenomenon and to keep from being tainted by it.

Meanwhile, Republicans are hoping that Kerry does what they most want: allow a photo-op with Madman Moore, or at least offer his film a rave review. As a high Bush campaign official says, "I can't wait to see what John Kerry says about the movie." Keep waiting. "John Kerry has not seen the movie," says spokeswoman Stephanie Cutter. He has been busy, she says. Notes a senior Democratic strategist: "John Kerry has stayed away from Michael Moore, and that's very smart."

But it's possible that Fahrenheit 9/11 may be having an impact on Kerry's war chest. Last week, the day before the movie's surprise victory at the box office was announced, Internet donations to the Kerry campaign climbed to a two-day fund-raising record of $5 million, with no special push from the candidate. Moviegoers may be plunking down their $9 at the multiplexes, then going home and e-mailing more money to the Man Who Isn't Bush. Says former Kerry campaign manager Jim Jordan of the film: "It is an exaggerated message from an imperfect messenger, but it might be the phenomenon that finally poisons the political atmosphere for Bush."

Can a movie do what a million get-out-the-vote initiatives have failed to do? Will an evening's smashing entertainment turn couch potatoes into political activists? Could Michael Moore's dream be George Bush's nightmare?

Reported by Desa Philadephia and Jeffrey Ressner/Los Angeles, Jackson Baker/Memphis, Betsy Rubiner/Des Moines and John F. Dickerson and Adam Zagorin/ Washington, with other bureaus